Transient Topographics

Re:Imagining Tourism in America’s Wildlands

Transient Topographics: Re:imagining Tourism in America’s Wildlands was my thesis project while pursuing my MFA of Collaborate Design at The Pacific Northwest College of Art. Utilizing an investigative approach to research and speculative/critical design methodology, the project explores and evaluates the impact of tourism on the communities adjacent to America’s public lands while interrogating past, present, and future notions of what the American Landscape is and can be.

Overview

Transient Topographics began where most things do - in my truck. In the summer of 2020, I hit the road in search of a topic for my MFA thesis. Over the course of 3 months, I drove 15,000 miles, visiting 10 states, 9 national parks, and I have no idea how much public land. During this first period of fieldwork, my research was generative and exploratory, prioritizing observation and reflection, especially during the first two months in which the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic made interacting with locals a challenge. As I moved through The West, I was made aware of a consistent conflict in the gateway communities on the periphery of America’s public lands, and began to realize that there was a common factor in the friction that I was observing — Tourism.

In 2020, tourism took perhaps the biggest hit that we’ll see in our lifetime. In the blink of an eye, the $9 Trillion behemoth of a global industry was simply canceled, as traveling became dangerous and congregating became illegal during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic illuminated so many flawed aspects of how our world worked, with not a single corner of our society left out of this great reckoning. In America’s gateway communities, what became clear was just how overly reliant they were on forces outside of their control to maintain their quality of life. Most gateway communities, having seen consistent growth for as long as anyone can remember, never anticipated that guests would stop arriving, or that they would find themselves struggling with their absence. Their economies, having been developed alongside our national parks, monuments, and wildernesses, were not diverse or nimble enough to navigate the complex uncertainty that the pandemic presented. As a result, communities around the country have had to rethink their relationship with tourism.

When I honed in on outdoor tourism as my area of inquiry, I decided to head over to that big ol’ ditch in Northern Arizona, The Grand Canyon. About as iconic a piece of public land as can exist in this country, The Grand Canyon seemed like the best place to investigate tourism in the wild. It was on my way to Grand Canyon National Park that I found myself in Kanab, Utah thanks to a particularly idiotic vehicular conundrum. As I waited for my truck to be inspected after getting stuck in Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, I realized just how absurdly entrenched in the wild Kanab is. Kanab itself is only about 14 square miles but is surrounded by millions of acres of public land, a vast collection of national parks, national monuments, and a slew of other land designations with a variety of administrators and mandates. It was instantly and abundantly clear to me that Kanab was exactly the type of community that was at the heart of this nebulous inquiry of mine. So, I stuck around to learn what I could about this small gateway community.

Kanab, Utah and the surrounding area.

After some time spent getting to know the desert and the people that populate it, I began to realize that the tension I was investigating in gateway communities wasn’t just a product of maladaptive social, economic, and infrastructural systems…

It was, at its core, a result of the ways in which tourism has changed the very nature of how both residents and visitors see, feel, and know the landscape. It was with this insight, gleaned from the foundational research that I had done during that first month in Kanab that I landed on a problem statement for this work.

How might we reimagine tourism on public land to illuminate emerging perspectives about how we conceptualize the American Landscape and our relationship with it?

It was with this question in hand that I decided to return to Kanab to continue conducting my research and work with discursive design methods to provoke critical reflection about the role that tourism plays within our social-ecological systems. From October 2020 to May 2021, I attended classes remotely while living in Kanab full-time.

My research strategy was immersive and investigative, a journalistic and auto-ethnographic approach to uncovering and understanding the diverse collection of stories, experiences, and values that co-exist in the community at the core of my inquiry.

Structured interviews. I conducted 50+ interviews with residents, visitors, and local/regional stakeholders. These interviews were all between 30 and 180 minutes in length and followed a constantly evolving discussion guide that allowed me to learn about their needs, struggles, and motivations. The stakeholder interviews included fewer questions about the participant’s personal life to allow room for questions about their area of expertise.

Ad-hoc intercepts. I cannot overstate how invaluable the less formal, ad-hoc intercept has proved to be in the pursuit of meaningful moments of truth in the field. Many of these initial engagements have evolved into deeper connections through which I’ve been able to explore this community in a very meaningful way. The impressions that I gathered from this part of my research were by far the most authentic and organic.

Surveys. Throughout the time in which I was working on this project, I created and distributed 5 surveys. These surveys were mostly geared towards trying to understand the traveler/visitor experience and were disseminated into my network mostly through social media and word of mouth. As a photographer with two social accounts geared toward landscape/travel photography and 20k+ followers, Instagram felt like a great place to connect with a diverse assortment of folks that either travel often or aspire to.

Sensemaking

Making sense of more than 8 months of ethnographic research and lived experience was a highly engaging and, at times, wholly overwhelming endeavor. It can be hard to see things clearly when you’re so deeply entrenched in a project like this and, as such, I found myself exploring a variety of ways to sift through all that I had learned. There were sleepless nights, gallons of coffee, and an ungodly amount of post-its. When all was said and done, I decided to focus on three distinct themes that had emerged from the most common and salient insights that I had gleaned through my research. Time, Space, and Secrets.

TIME

The density of natural attractions in the area makes visitors feel like they have to do it all leading to FOMO (fear of missing out) and/or burnout. This leads most visitors to try and do too much in a trip which only leaves room for quick and relatively shallow interactions with communities along their route.

Time spent, or lack of it, contributes greatly to tension within gateway communities as, over time, residents being to resent visitors, especially those that are in too much of a hurry to genuinely connect. There is also a strong sense of a legacy in those with familial ties to the community which leads to challenging power dynamics between long time residents and folks that are new in town.

Visitors often underestimate the time it takes to both mitigate visitor density and traverse Utah’s terrain, as well as the physical and emotional cost that traveling in the desert can have. This leads to a poor visitor experience.

Kanab’s tourism strategy is actively trying to entice visitors to stay longer, with one more night being the current goal.

Thanks to institutionalized temporal guidelines like the 5 day/40 hour work week and the way America allocated vacation time, most folks feel an extreme sense of time scarcity while traveling.

Space

Thanks to population growth and increased visitation, there is a tremendous lack of affordable housing in gateway communities because:

The increased profitability of vacation rentals has lead many homeowners and landlords to utilize their space for short-term vacation rental instead of long-term housing.

Increased visitation has lead many out-of-town folks to purchase a second or third home as an investment property or a means of generating passive rental income.

Increased popularity has lead to an influx of new business, mostly aimed at facilitating the visitor experience. These businesses bring in staff which require housing. Lack of housing has left many of these businesses short-staffed.

Existing housing stock is often poor quality and new development is usually focused on meeting speculative demand rather than fulfilling the currently unmet needs of residents.

“Zoom Towns” becoming more common as many remote workers and digital nomads settle in gateway communities. Their salaries are often reflective of the cities in which their employers are located rather than where they live.

There is consistent conflict within the community about how space is allocated thanks to the growing tourism industry.

Secrets

Visitors are looking for more authentic experiences which has lead local tourism business owners to supply their local knowledge to meet demand.

Local secrets are seen as “natural assets” in the tourism industry and are used to disperse crowds when overcrowding begins to affect visitor experiences.

Residents don’t visit their favorite spots anymore because they rarely have an enjoyable experience these days.

The problem isn’t just exposure, access has also increased greatly over the last few years as the internet and navigation technology have made sites easier to locate.

Land management organizations have begun instituting a variety of systems and policies to limit access to parks and monuments.

Design Criteria

Discursive. From the outset of this project, I was interested in working within a critical/speculative design context. This project was meant to act as a suite of design provocations not solutions. I did not want these to read as suggestions, as an uninvited consultation as to how southern Utah should address the situation on the ground. Instead, I wanted to operate in a space between reality and the impossible, a place where I could play with ideas of progress, especially because progress looks like so many different things to so many people. The goal of this project was to get folks thinking and talking — to instigate critical reflect among both visitors and residents about their role in it all.

Wild Caught. It was important to me that the subjects of my reimagining be based on real experiences that I had and were not just fictional notions of what could be. Each of these imaginaries that I have constructed comes from tensions, concerns, and metaphors that I’ve uncovered during the various phases of my research. They are each in response to something real, an existing set of systemic and cultural artifacts that I’ve elaborated upon.

Aesthetic wayfinding. Lastly, I wanted to stay away from concrete temporal notions. We each have a unique relationship with time and I wanted viewers to come to their own conclusions as to when these imaginings might take place. I was interested in how to use different aesthetics, side by side, to ensure that viewers had to navigate through time on their own. It is very possible, even probable, that these imaginings are at home in a future that is much different from our own. However, I did not want the aesthetic choices that I made to solidify that notion before viewers at the opportunity ask themselves “but when?”

The Vingettes.

I have approached these imaginaries as thought experiments, as simplistic “what if’s” that found me in the field. They oscillate between possible, plausible, and preferable, depending on the viewer, and while I find aspects of them to be quite provocative and salient, they are most definitely not things that I think should exist. They are, instead, a reaction to the research that I have done, the people that I have spoken with, and the notions that I have found to live out here amongst the sage and the juniper. They are presented as vignettes, as small windows into a world that doesn’t necessarily exist.

Kanabucks

Time is everything. Time spent, or lack of it, is the major point of tension within gateway communities. Thanks to a variety of societal factors, most travelers live in a state of constant perceived time scarcity. While traveling, many will try to get the most out of an experience by packing as many people, places, and things into it as possible. In the wild, this often saturates the most popular natural attractions and leads to not only a diminished visitor experience but also a more shallow interaction with a place and its people. The local discount is a byproduct of a tourist economy and only exists in a place that sees considerable visitation. This vignette, framed as a whiteboard video, imagines a future where Gatewaze, a digital currency platform, has helped Kanab, Utah institutionalize the local discount as a way to incentivize visitors to stay longer.

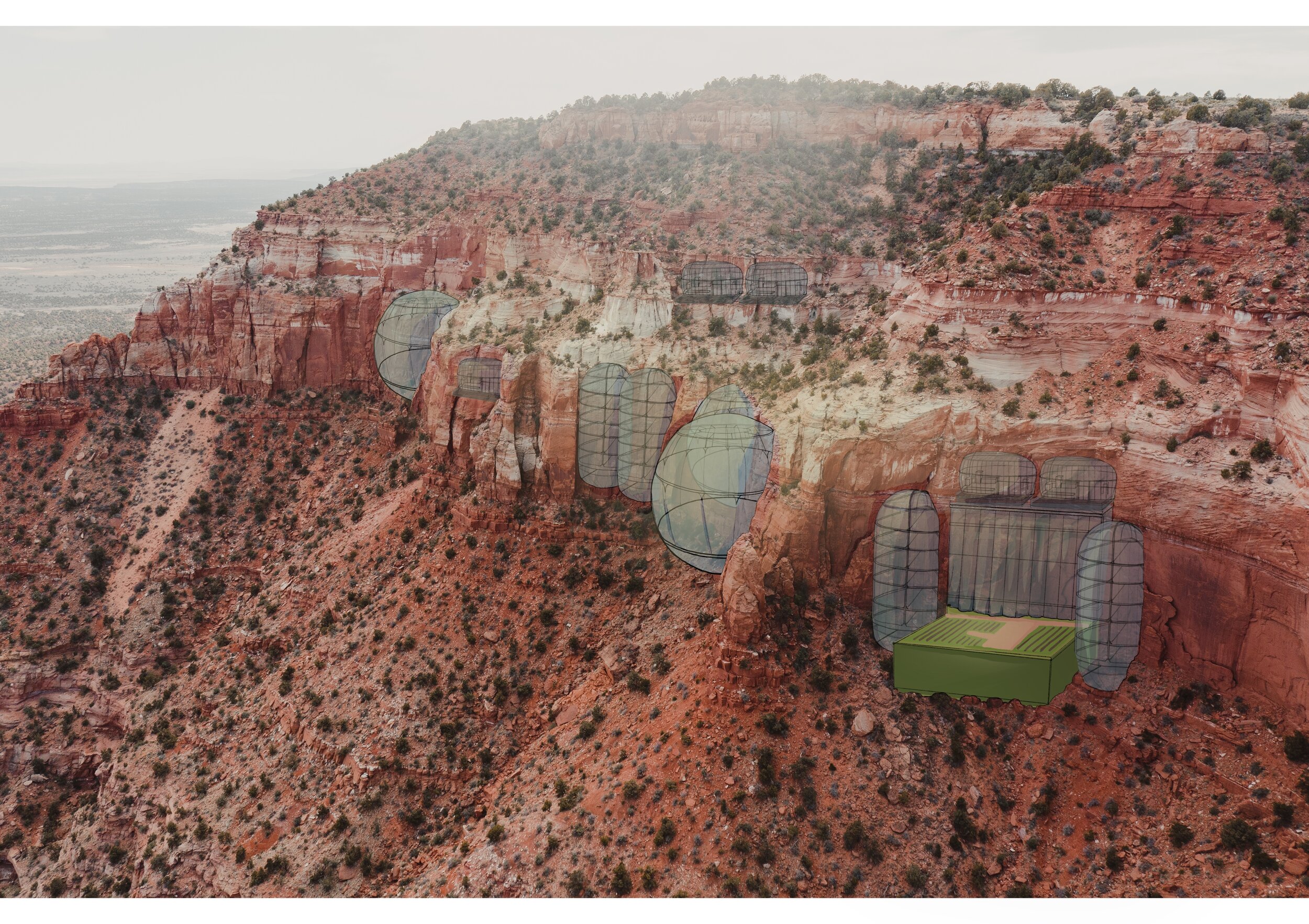

DOMOS.

There is consistent conflict within gateway communities about how space should be allocated. Residents and visitors have inherently different spatial needs within a tourist economy and trying to accommodate both can lead to much tension. With the ongoing popularity of websites like AirBNB, vacation rentals are becoming significantly more profitable than long term rentals. Thanks to this and the influx of new residents in what is being called the new natural amenity migration, there is a huge need for affordable housing in many gateway communities. Despite this need there are also many residents who believe that land would be better used by extractive industry than by housing developers. In this vignette, DOMOS is a new affordable housing development that is being built by Red Sands, a pioneer in sand mining and glass fabrication technology. DOMOS is designed to be used for both transient and residential housing, depending on community needs.

A.N.A

In the wild, the local secret is quickly becoming a thing of the past. As visitors to our wildlands find themselves looking for less popular and more authentic experiences in the outdoors, they inherently perpetuate the very crowding that they are looking to avoid. Local secrets are seen as “natural assets” in the tourism industry and their offering by land management is used as a tool to disperse crowds when overcrowding takes hold of natural attractions. Through my research, I have learned that, while there are so many factors in this, the biggest driver of change is navigation technology and what it has meant for access. In the past, the local secret was much safer because finding it was often challenging and even dangerous. In this vignette, I have imagined A.N.A, the navigation system for an autonomous vehicle, and how it might function as a part of the outdoor tourism systems of the future.

You can read the full thesis here.